The Data Collection and Management Plan

The Threads of the War Game Design

In the early stages of a project (usually early in the "Design" phase), various threads begin to emerge. The Sponsor's objective and the associated issues should be identified. Some issues that are particularly complicated may be decomposed into sub-issues.

In terms of the evidence that will be needed from the game, essential questions (EQ) should be emerging. The EQ should be associated with issues (and sub-issues when appropriate). Individual issues may have just one or a number of essential questions associated. The essential questions should be framed such that, if they are answered during the game, that will provide the needed evidence to resolve the issues that were raised by the sponsor.

Looking at a proposed "answer" to an essential question should immediately show if sufficient evidence has been accumulated. If the "answer" contains considerable uncertainty then the EQ probably has not been adequately addressed. Should that be the case, there might be some way to address the EQ in another way (with a follow-up war game or through methods other than wargaming). Otherwise the sponsor will need to be told that an EQ (and associated issue) has not been resolved and will need further study.

Aspects of the required scenario should also begin to appear during the Design phase. The Sponsor may have a particular scenario in mind and provide it to the team or, as the objective and issues become clearer, these may dictate clearly many of the elements that will be required in a tailored scenario.

Along with elements of the scenario a list of players for the game should be taking shape. These players may be identified by the position title that is required in the game, such as "brigade commander", or the identification may be a named individual, or it may be both.

Along with the players, some clarification should emerge of the information they will require to perform their roles within the war game. It should also become clear what information can be extracted from the players and how they will need to behave to address the essential questions. Apart from these inputs to and outputs from the war game, there is also data that will change as the war game proceeds and should be provided to the players so they can play their roles. This data will be called feedback data.

Another thread that will be emerging as the Design phase proceeds is the identification of the methods, models, and tools that will be required to support the players and other aspects of the war game.

Although not that evident in the early stages of a wargaming project, there is a ongoing need to track requests for information and, as they are identified, the constraints, limitations, and assumptions associated with the war game.A Data Collection and Management Plan (DCMP) is means of collecting these important aspects of a wargaming project in one location. Early in the Design phase a DCMP template should be established. In it, all available information should be recorded. And, as new information emerges, it should be added to the DCMP template. The DCMP should be a "living document" and revisions and additions to it may be made up to the time of executing the war game itself. Of course, the sooner entries in the DCMP can be confirmed the better, but flexibility in adjusting it needs to be retained throughout the project.

The DCMP Spreadsheet

As planning for the wargaming project continues, it will become clear who needs to be included as a player. The team can start to compile lists of data associated with the war game. This should include the data players (and models or simulations) will need. The data should also include feedback data: the data that will be provided dynamically as the game unfolds. Players will use this feedback to determine to consequences of their decisions earlier in the game. Finally the data should include the data coming from the game, from the players, and from any associated methods, models, and tools that will be needed later to analyze the game.

For seminar war games, where data collection may be limited largely to a record of the discourse between players, the MOMs would not often be quantitative measures. Data collection is more likely an assessment of qualitative views or of military judgement. Even though most seminar war games would require a far simpler DCMP than seen in many other forms of game, a DCMP is still valuable in designing a scenario that will hit on the issues that emerge from discussions with the sponsoring organization. During the conduct of the seminar war game, the DCMP provides a useful checklist to ensure that no relevant issues have been overlooked; using a DCMP should ensure that the study team will avoid reaching the end of a game only to discover that data on some important issue was never collected.

Generally a DCMP is developed in a

spreadsheet format, as that is a

convienient and familiar tool. Apart from the contents already

indicated, columns can be added for many more elements.

Generally a DCMP is developed in a

spreadsheet format, as that is a

convienient and familiar tool. Apart from the contents already

indicated, columns can be added for many more elements.

Across a row in a DCMP spreadsheet, one should find an indication of the issue to be addressed (derived from the sponsor's ojective). If an issue is particularly complicated, it may be decomposed into a number of sub-issues. Then further to the right of the issues/sub-issues will be the essential element of analysis (EEA). And to the right of this will be a measure of merit. Note: there may be more than one EEA for each sub-issue, and more than one MOM for an EEA. For a MOM, there may be several data elements (DE), if the decomposition is to that level of details.

For example, an EEA may deal with casualties, which could result in a collection of several MOMs or DEs. It may be necessary to collect BLUE and RED casualties, and these casualties might be sub-divided by personnel and vehicles. And there could be further categories for BLUE-on-BLUE casualties or collateral casualties to the civilians population.

While the obvious purpose of a DCMP is to develop an inventory of expected data (at the levels of MOM and DE), by extending the DCMP to the right, the DCMP encourages the development of elements of the scenario -- clearly no data can be collected for an issue/sub-issue if there is not a point in the scenario where the players are confronted by it. To extend the previous example, no data will be collected on casualties unless something in the scenario creates the potential for casualties. And further, if collateral casualities to a civilian population is a concern, there has to be potential within the scenario for such casualties to occur.

Scenario Elements

As aspects of a suitable scenario become clear, they should be recorded in the DCMP. By placing scenario elements appropriately opposite the sponsor's issues and the essential questions, the linkage will be clear. If certain issues or questions need greater or lesser attention, the consequent need to adjust the scenario will be apparent by reading across the appropriate rows in the DCMP.

Players

As columns in the DCMP to the left are filled in, it should be clear what sorts of players will be required for specific parts of the war game. If an issue deals with logistics, it is likely players with familiarity with supply and maintainence will be required. If an issue deals with air support, personnel from the air force are likely going to be needed.

This column in the DCMP also provides space for specific names of players. For example, the sponsor may wish to have certain individuals involved. It may be that they are proponents of some specific new capability. Or it may be that they have proven particularly adept in the past in the sorts of decision making that will be at the heart of the war game. Or they may be subordinates from the sponsor's organization who are available or who should be given the opportunity to make a certain contribution to the game.

Player Information

Information that players will deal with in a war game comes in three forms. There is the data that is required to get the game started. This may be the order of battle (ORBAT) of the forces a player can command. Or it may be performance characteristics of specific systems, e.g., the range and lethality of a weapon system. Sometimes this data is not provided directly to players, but rather is used within a computer simulation that supports the war game. Players may be given a summary of this information, although the simulation may require very detailed tabluated material, such as lethality of a round in increments of range.

A second form of information in a war game is the feedback information that players get from a game as the game progressed. This may be an update on rounds fired or rounds remaining for a specific platform. Or it may be a report on casualties inflicted on an opponent or absorbed by the players own forces.

A third form of information is the data that is collected specifically for analysis. While the analysis function should include collection of data of the other two forms, this form may include data that players never see. It may, for example, include comments from observers on how and why certain players made their decisions. For example, if players have developed a misperception of how operations are unfolding, it is important for the analysis to record this, even though players at the time may be oblivious to it.

Methods, Models, and Tools

A column within the DCMP spreadsheet can be set aside for the Methods, Models, and Tools (MMT) that pertain to a particular issue, sub-issues, or essential element of analysis. If the game is a short small seminar game the only MMT used troughout could be "Facilitator's Judgement". But more elaborate MMT can also be used. For example, if a sub-issue represents some aspect of ammunition consumption, the associated MMT might be a combat model that can represent engagements and track rounds fired. Once the column associated with MMT has been completed, it can be used to manage the inventory of MMT. For example, if a combat model is a requirement within the DCMP, then the analysts and designers will have to allocate resources to ensure it will work as intended within the game struture.

Note that even if aggregated MMT amounts to a repeated use of "Facilitator's Judgement", the facilitator and the team must ensure that the facilitator has appropriate competency to support the full range of issues that may emerge during play.

Scheduling Events

The DCMP provides a mechanism to schedule certain events. There can be "Location" and "Time" indicators in the right hand columns to indicate where, during a scenario or in a MSEL (master scenario event list), an opportunity would arise to observe the issue in question. If the issue were important and there had been no opportunity to collection reactions to it, then the MSEL would have to be adjusted accordingly. Hence, the scenario design must accommodate the analysis plan.

For smaller games, the use of the DCMP for scheduling seem be of little value. However it can provide a checklist to ensure that issues that are expected at a particular point, arise at that point. If they do not, the facilitator or control cell will have to face a decision to introduce the issue at some other time, or to accept that no evidence on that issue will be captured.

For larger games, say where there are many players and they are are dispersed in a training area, or where the play extends over several days, the DCMP scheduling mechanism assists in the economical management of data collectors and observers: they will be deployed at the right time and right location.

The Extended Data Collection and Management Plan

As plans for a war game develop, the wargaming team will encounter situations where they need information. The source is frequently the sponsor or the sponsor's staff; so the responsiveness in filling these needs lies within the control of the sponsor or other leaders in the sponsor's organization. The wargaming team should use a consistent mechanism to raise and track requests for information, which are often directed to the sponsor's staff for a response, but alternatively these may have to go to outside agencies that have relevant expertise or specialized knowledge.

As indicated, some RFIs may be directed to agencies other than the sponsor's staff. For information on the opposing force, for example, the wargaming team may go directly to some intelligence organization. For cultural factors in the area of operations, responses to an RFI may be sought from embassy staff in the corresponding country or from the academic community. For weapon and sensor characteristics there may be engineering agencies that have test data on appropriate systems.

In larger wargaming projects the tracking of RFIs – where they were routed, when a response can be expected, and confirmation that a reply has fully satisfied the corresponding RFI – can be significant administrative duty. Placing a "marker" in the DCMP for each RFI ensures these requests are readily apparent. By inserting them into the DCMP opposite specific issues/sub-issues clarifies the linkage: if a specified RFI is not satisfied, then the issue against which it has been placed is unlikely to have results that will satisfy the sponsor.

As discussions with the sponsor and the sponsor's staff are taking place, the war game team is likely to encounter constraints and limitations, and be forced to make assumptions to fill in gaps. Sometimes, pending a response to an RFI, assumptions will have to be made temporarily to move the project along without having to suspend activities because an RFI response is not forthcoming.

An extended Data Collection and Management Plan is a useful mechanism to track RFIs and CLAs. Placing markers within a DCMP, typically to the right of the components identified above (EEAs, etc.), links each RFI or CLA entry to issues and sub-issues of the sponsor. Thus they provide traceability back to interests of the sponsor. It is then possible to connect a failure to get a response on an RFI or to the restrictions from a constraint or limitation back to the sponsor's expectations. This in turn can have an impact on game design and development and on the results that can be provided at the conclusion of the project. Since the RFI and CLA are specifically linked to the interests of the sponsor, these links might be used as leverage to overcome impediments to proper preparation for a game or to reduce expecations of how well the game results will cover issues where an impediment has not been overcome.

Some contraints set by the sponsor may be on the "grand scale" and affect all aspects of a wargaming project: e.g., the overall budget, the due date for delivering the final report. Other constraints may be more localized to specific issues. The sponsor might specify that a particular combat model be used to adjudicate firefights, or that certain individuals be present as players when a given topic is discussed, or that certain technologies be used by players so their effectiveness can be determined. By embedding the appropriate links in the DCMP across from the affected issues/sub-issues the localized effect of these constraints will be clear. Similarly for RFIs that have not been answered in a timely fashion (usually resulting in an assumption across the same row in the DCMP).

When including RFIs and CLAs in a DCMP only a link or some keywords should be inserted into the spreadsheet to keep its size under control. Separate lists or notebooks or databases can be kept of the necessary details.

Position of Columns within a DCMP

The positioning of columns is at the discretion of a user, and some users may eliminate some of the recommended columns or add new ones that are locally more useful.

The column on constraints, for example, may be placed adjacent to columns on issues. Linking constraints so clearly to issues facilitates a "negotiating process" with a sponsor over the consequences of some particular constraint that has been set by the sponsor. If the sponsor can more clearly see the ramifications, it may be possible to have the constraint lifred. It may be that having the sponsor add resources to a project or extend deadlines will allow one of the sponsor's issues to be better addressed in the war game.

A user of a DCMP may wish to add a column on reference documents. Thus an issue on logistics will be covered in the game only after all concerned have read the current doctrine on logistics.

Users of a DCMP need to appreciate it is a tool to assist them. If the DCMP needs some additional columns, add them. If the positioning of columns obscure some aspect or if a rearrangement will bring out some critical aspect, then make the appropriate changes. If columns recommended here are inappropriate for an application, then delete them. The intention of using a DCMP is to reduce workload and clarify matters, not the reverse.

Various Additional Extensions to the DCMP

While not necessary within a DCMP, a developing DCMP may be elaborated with various additions. For example columns can be added for the following:

• titles of doctrine or training manuals that should be consulted so observers have more contextual information on some potential event

• external agencies that might need to be consulted or that might needed to approve some activity, e.g., range control or air traffic control.

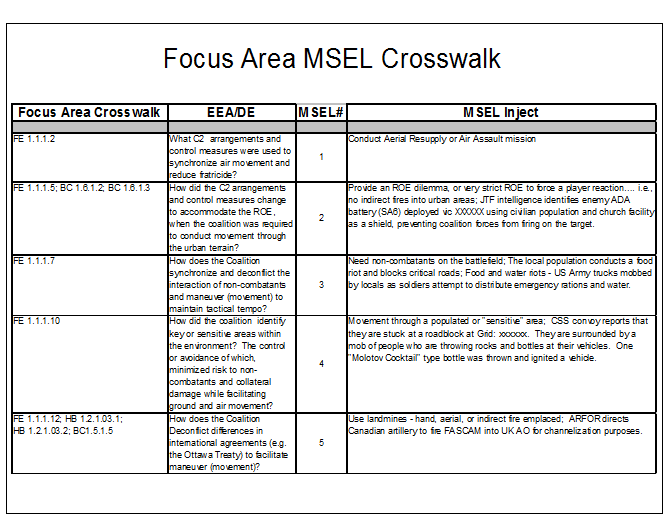

Scenario Crosswalk

The Analysis Handbook also provides a mechanism to

crosswalk from the issues that are the focus of a war

game to scenario design -- from the Essential Areas of Analysis within the Data Collection and Management Plan (DCMP) to

the Master Scenario Events List (MSEL). This is the means to do a double check that important issues for data collection

will be afforded opportunities within the scenario to see how participants deal with them. Note that it is probably risky

to have an important issue without some corresponding activity in the MSEL, although it could come up merely by chance.

However there may be entries in the MSEL that have no corresponding issues from the DCMP; specifically, there may be items

in the MSEL that provide some extra realism for the players, or that can provide some other secondary function, e.g., events

to develop team cohesion or to practice a routine that may be necessary later in the scenario.

The Analysis Handbook also provides a mechanism to

crosswalk from the issues that are the focus of a war

game to scenario design -- from the Essential Areas of Analysis within the Data Collection and Management Plan (DCMP) to

the Master Scenario Events List (MSEL). This is the means to do a double check that important issues for data collection

will be afforded opportunities within the scenario to see how participants deal with them. Note that it is probably risky

to have an important issue without some corresponding activity in the MSEL, although it could come up merely by chance.

However there may be entries in the MSEL that have no corresponding issues from the DCMP; specifically, there may be items

in the MSEL that provide some extra realism for the players, or that can provide some other secondary function, e.g., events

to develop team cohesion or to practice a routine that may be necessary later in the scenario.